Last week we posted a general outline of teaching students to learn conceptually. Today we apply the outline to an actual class — 6th grade social studies.

Here’s the context: The teacher worries that it might feel abrupt to suddenly begin being explicit about conceptual learning in the middle of the unit. A potential solution? Use the facts they already know and the conceptual relationships they’ve already explored (though without being explicit about concepts and learning conceptually) for a one or two class period lesson on learning conceptually. Students have been exploring revolutions across time periods but with a focus on the 17th and 18th Centuries. The statement of conceptual relationship (generalization or statement of inquiry) is posted in the front of the class. Here are the lesson steps.

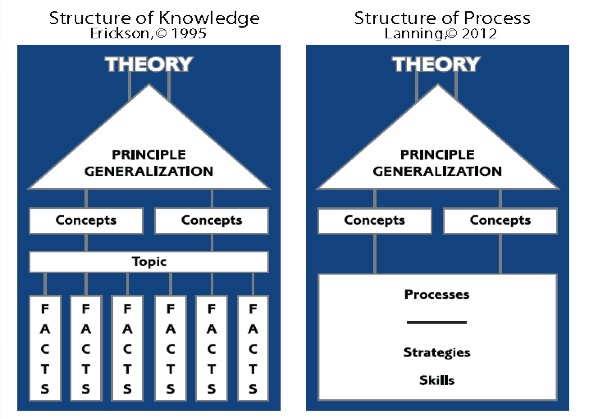

- Students discuss in pairs: What makes someone an expert? How do they remember so much? Teacher records responses on the board. Teacher says, I’m going to let you in on a little secret about experts. They organize information in their heads through something called the Structure of Knowledge. This helps them to remember things more easily and helps them to unlock new situations on their own. You have already begun learning in this way, we are just going to be direct from now on about this type of thinking and learning.

- Teacher shows the Structure of Knowledge (or Structure of Process if you teach language, arts or music) with their current unit’s example. Starting from the topic level and the facts, the teacher briefly explains each component, ending with the concepts (revolution, power, society, rights) and the statement of conceptual relationship: Social revolutions change the power relationships in society through the extension and limitation of our rights.

- Students sort concepts and facts into piles. Then come up with a working definition of each category — they will probably say things like concepts are more “general” and facts are more “specific”. This is a great opportunity to teach them the word “abstract” as one of the key definitions of concepts. In this case each small group gets three piles. The concepts are capitalized just for you to see, but would be the same size so students have to figure out which one is different for each pile. They already have experience with these facts and concepts so this should be pretty easy to do. The point is to see the difference between concepts and facts.

REVOLUTIONS

Russian revolution

Industrial revolution

The Enlightenment

AUTHORITARIAN RULE

King Lois XVI

King Charles I

Emperor Nicholas II

REVOLUTIONARY THINKERS

John Locke

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Mary Wollstonecraft

- Statements of conceptual relationship: each small group gets the following four statements and discusses these questions. What are they? How do they help us organize information? How would they help us figure out new situations without the teacher there to help us?

- Social revolutions change the power relationship in society through the extension and limitation of rights.

- Revolutionary ideas often cause people to question the traditional power structures in a society.

- Access to information and strong reasoning leads people to question traditional lines of authority.

- People thinking for themselves as opposed to simply listening to authority often creates a period of change and innovation.

- Improving statements of conceptual relationship: Start with the basics – no proper nouns, no-no verbs = is, are, have, impact, affect, influence. Explain why each are the rules (proper nouns are facts, they don’t transfer; weak verbs don’t tell us enough about the relationship between two or more concepts). Students evaluate these statements and improve them:

- The French Revolution changed the power relationships in society.

- Social revolutions impact the power relationships in society.

- Rights are often extended or limited in social revolutions.

- Synergistic thinking: Students receive the following statements and facts, mixed up. They match the conceptual statement with the facts. Teacher explains the power of synergistic thinking.

- Access to information and strong reasoning leads people to question traditional lines of authority. (Enlightenment, French)

- Sometimes revolutions against authoritarian rule can eventually lead to even worse authoritarian rule than before the revolution. (Cuban, Russian)

- Transfer: Show them a new revolution that they have not seen such as the American or the more recent Egyptian Revolution. They are to choose which of the above statements best helps them to unlock the new situation and why.

- Writing our own statements: Teacher tells them that we abstract our own statements by asking ourselves, “What is the relationship between two or more of the concepts?” and use the facts to help us answer it. They try it out with, “What is the relationship between revolutions and rights?” They have to answer it in their own words. Give them the sentence starter, I understand that _____. It would be a great idea to give them a simple rubric at this point and ask them to evaluate where their statements fall in relation to the rubric.

- Reflection: Spend as much time on this as possible through discussion.

- What is the difference between a concept and a fact?

- How is learning about a concept different from learning about a fact?

- What is the definition of and importance of conceptual relationships?

- How do we improve statements of conceptual relationships?

- What are some ways to discover conceptual relationships?

- How do they help us to unlock unfamiliar situations?

What do you think? Is it worth the investment of class time to teach them about a different and better way to learn? I think so! Don’t delay!

You KNOW I LOVED this blog Julie! Thanks for helping teachers understand Conceptual teaching and Learning. Once they have taught students deductively by posting the Generalization–they can also practice inductively drawing the generalization from students through questioning. GREAT JOB JULIE! Lynn Erickson

Wow, thanks so much, Lynn! Hope you are enjoying seeing the continuation of your work from your lovely lake house. 🙂